- Home

- H. G. Nelson

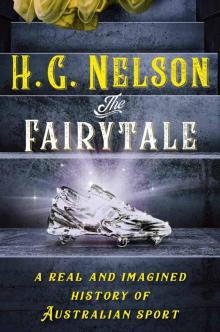

The Fairytale

The Fairytale Read online

About The Fairytale

A sporting nation is only limited by its imagination. Every time this story is told it changes; something is always added, embellished or dropped from the run-on side.

For more than thirty years, H.G. Nelson has been finding the poetry in the punt and humour during half-time. Now, he turns his keen eye for facts and folly to the illustrious history of our great sporting nation.

In his trademark fast and furious style, H. G. dives deep into the moments that have truly made us who we are. He reminds us of our leaders’ great sporting triumphs, from Harold Holt’s swimming to John Howard’s bowling; rewrites the record on legends such as ‘Aussie Joe’ Bugner and Jack Brabham; and explains why Australia’s reality TV is the best in the world.

The Fairytale is H.G. Nelson›s magnum opus – an all-encompassing, no-holds-barred history of Australia at play, told through the stories of our sporting highs, lows and middles.

ALSO BY H.G. NELSON

Petrol, Bait, Ammo & Ice

The Really Stuffed Guide to Good Food 2006 (ed.)

Sprays

My Life in Shorts

Contents

Cover

About The Fairytale

Also by H.G. Nelson

Dedication

INTRODUCTION The Fairytale

PART 1 HISTORY

Grand Finals and pre-match entertainment

From humble beginnings to a monster that threatens to overwhelm the game.

The national agenda

Prime Ministers who came, served and were forgotten.

The Olympics

Medals, mates and memories from the five-ringed sporting circus.

Rugby league

The noble origins of the Greatest Game of All.

PART 2 HEROES

‘Aussie Joe’ Bugner: The name says it all

A brief boxing memoir in shorts and gloves.

The captain of the team

A role model for success at the very top.

Rugby league is war

Conflict and outrage on and off the field.

Tony Abbot: The Punching Prime Minister

Our nation’s heavyweight champion in action.

Jack Brabham: The best of the lot

An early win in an illustrious motor racing career.

PART 3 LEGACY

Horse racing

Everyone’s a winner at The Everest.

Cricket’s Holy Grail

Don Bradman’s lost pitch, rediscovered.

Golf: If it’s not up it’s not in

The grip it and rip it game is back in fashion.

Sports rorts: Everyone knows everyone does it!

The not-so-new sport of pork barrelling.

Songs of praise and songs of redemption

Remembering the glory days of the Greatest Game of All.

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Copyright page

To the here, there and everywhere duo of Lucille Gosford

and Kate Gosford, with thanks for the

wonderful Wagstaffe years.

Introduction

THE FAIRYTALE

A real and imagined history of Australian sport.

SPORT HAS BEEN PART of Australian society for centuries. Everything was humming along nicely for tens of thousands of years, but in 1788 the whole shebang took a weird righthand turn when the First Fleet burst in through the Heads under full sail with senior referee Arthur Phillip at the helm. He blew the siren on the old sporting codes and overnight different, new-fangled sports with crazy rules were on top of the weekend agenda.

Instead of nationwide participation by the whole community, the citizens of the new colony were suddenly only interested in the big game and the big game players. They liked the ones who could go hard early and kick clear as the field turned for home and headed up to salute the judge. The new settlers loved the excitement of seeing a conveyance come from behind and nab a convincing win in the shadows of the post. Suddenly the rules were there to be bent and exploited and it did not take long for the lurkers to unleash their cheating ways.

The Fairytale ambles along the winding track of time from Phillip’s first colonial tweet on the Thunderer right up to and beyond the arrival of the Olympics to south-east Queensland in 2032.

A sporting nation is only limited by its imagination. Every time this story is told it changes; something is always added, embellished or dropped from the run-on side.

This is not a tale of who won and where. How it was won and why. Or why it went down to the wire before hitting the S-bend of disappointment and was flushed away. The real, full-time scores can look after themselves on other platforms in other books. The record-keeping industry provides valuable employment opportunities for those who stand back with the pencil poised over the blank sheet of paper.

From high in the grandstand, The Fairytale uses the eight-by-ten binoculars to cast a gaze across this wide sunburnt land of drought and flooding rains. From this magpie-eye vantage point it is easy to see that sport is now central to the very idea of Australian society. That is the 12.78 millionth time that fact has appeared in print in Australian media since 1788.

Stating the bleeding obvious, these chapters are plucked from the nation’s real and imagined sporting jamboree. It is not the whole story. It is a dip of the toe into the vat of victory featuring remarkable results and an improbable cast of characters, some of whom actually lived.

It is a dip of the toe into the vat of victory featuring remarkable results and an improbable cast of characters, some of whom actually lived.

Horse racing was the first of the European introductions, with races run around Sydney’s Hyde Park not long after the anchors dropped at Farm Cove. Punting was central to the race day experience. Sports betting kicked off as soon as the first convicts and crew staggered off the forgotten ships of the First Fleet, the Lady Penrhyn and the Prince of Wales.

Sporting types freed from the shackles of conservative England were prepared to bet on anything. This was soon demonstrated by the big turn-outs for fly races up the walls of the first pubs in The Rocks around Circular Quay in Sydney.

The whole ‘long may we play’ caper really took off in the early 1800s. The first Sydney Cup was run in The Fortune of War pub on 12 June 1811. The five-pound purse and a bottle of Arthur Phillip claret (1792) were won by The Pride of Potato Point, a big blowie from the Narellan area, who nailed Cracklin’ Dopsie, a biting march fly from the Upper Hunter. The big buzzing noise from Scone was nabbed in the final bound in a desperate finish that went down to the pencil line on the cornice behind the swinging doors in the front bar.

Soon local megastars emerged from the pack. One of Australia’s early greats, maybe our original GOAT (as in ‘the greatest of all time’) was William Francis King. Billy was known to anyone who put a bet on him as ‘The Flying Pieman’. His record speaks for itself. Bill’s sport was pedestrianism. This lark, now lost, was a big noise at the time when Billy went sauntering. No one could touch him on the stroll. He dominated over all distances, in all events and in all conditions. He was the Ian Thorpe, the Dustin Martin, the Bart Cummings, the Winx of his era, with a dollop of cream to go with the strawberry on top of the Royal Show blue ribbon–winning cake. He was that good.

Bill blew into town in 1829. He was a schoolteacher by trade, but gave the chalk away to slip behind the slab and pull beers at The Hope and Anchor. The demanding hours in hospitality meant he had no time to train. Bill dropped the bar work and turned his hand to making pies. He sold ‘the four and twenties’ waddling around Hyde Park in downtown Sydney. The park was developed as a central sporting venue in the early days of the NSW colony.

The waddling baker excelled at walking enor

mous distances in a very short time. He inherited the ‘Pieman’ mantle from Nathaniel McCulloch. Nat was an A-grade pie-making rambler but a bit silly with it. McCullouch was often up before the beaks of Olde Sydney Towne for running amok and disturbing the peace with his bad behaviour. On one occasion he was fined five pounds for attempting to cut his own throat.

The Flying Pieman, Billy King, made his mark early. On one occasion he sold pies to passengers boarding the ferry in Sydney, then ran the eighteen miles to Parramatta to off-load the remaining unsold tartlets, cinnamon scrolls, finger buns and savoury quiches to the same passengers as they got off the ferry. That is some effort. All that way on foot, keeping the pies hot and the flies off was an astonishing effort. With this fantastic display the mantel of top dog was passed from McCulloch to the King.

Bill saddled up Shanks’s pony and walked because there were not many ways of getting around the NSW in the early days. Boat, horse and carriage were about it, apart from self-propulsion with the pedal extremities.

One of Billy’s very big walks was a 192-mile canter in forty-six hours. The venue was the Maitland racecourse. He completed 206 laps, attracting big crowds as the nights turned into days. Remember these were simpler times. There were fewer must-see night-time attractions. Watching a fit pieman stagger about the local racecourse fuelled conversation for weeks.

The Prince of Pastries loved lugging weights, big weights. He was a whizz with weight. They say trackside weight is a great leveller; not for the Pieman.

As Bill outlined in a profile for ‘The Walking Week’, a column written by Devon Sprode and published in The Argus:

Devi, weight is no heavy burden. It’s all in the mind. Honestly when I pick a hundred-pound lump of Sydney sandstone that I have to deliver to a building site in Warwick Farm, of course I feel insane. Who wouldn’t? But honestly, Dev, the first ten steps are the hardest; after that it becomes a blur. And remember I am carrying eight dozen hot pies to drop off at Casula along the way. So, I never go hungry.

The King of Flans loved company on the road. When he took on the great Campbelltown to Sydney Challenge in January 1830, he carried a thirty-two-kilo dog as a companion. He backed up and did the Sydney to Parramatta Christmas Eve Mini Sprint and was handicapped by the stewards with an adult goat. It was described by Sprode in that week’s column ‘as a double goat act’.

The Footloose Flyer had a crack at a range of novelty events. He once beat the mail coach from Sydney to Windsor using a single breath.

He loved making it fun. His run a mile, walk a mile, push a brick-laden wheelbarrow for a mile, drag a cow in a carriage for a mile, walk backwards for a mile and walk for a mile over stones placed five yards apart was a Easter happening that drew very big crowds. His best time for this early multi-discipline ‘triathlon’ style event was a swift twenty-three minutes. A record that still stands.

He created some of these idiotic challenges with the help of letter writers to ‘The Walking Week’ column who responded when he threw down the gauntlet and asked, ‘Well punters, what do you want me to do next?’

Often as an extra wriggle tacked on to his promenading there was an eye-watering food challenge for the crowd who gathered at the finish line. He once polished off nine familysized pies and a dozen beers after finishing first in The Gong and Back Charity Fun Run. This stomach-extending pie-a-thon completed a memorable day out for families, who got the crumbs. And it gave kids memories for a lifetime.

Billy King did much to establish the new agenda of sporting and culinary traditions in the colony.

He loved a flutter and took on all comers. Most of the bets were set against him achieving his impossible goals. Sadly for slow-learning punters, there were tears before bedtime as they usually lost.

By the way, is it time to begin a national conversation about celebrating the deeds and contribution to Australian culture of The Pieman, with a Day of Walking Wonder featuring all-age events over serious distances? What a great contribution this day would make to the build-up to the torch relay blast-off for the 2032 Brisbane Games.

The highest levels of state and federal government need to set up an all-party committee to probe the possibility of a waddle from Dubbo to Darwin via Uluru and The Alice. This ramble would bring the nation together as Australians would be glued to social media platforms for live updates as they followed the progress of a hot international field. The world would be watching.

Old-fashioned pedestrianism had echoes in the Melbourne to Sydney Run first staged in 1983, with the last international line-up flagged away in 1991. This one stopped the nation for days. It was a very popular saunter up the Hume sponsored by the Westfield shopping mall people. The idea was that Australians thinking about the Melbourne to Sydney amble would waddle off to the nearest Westfield in their area and buy up big. It was a 960-kilometre race and Cliff Young, the gum-booted Colac dairy farmer, set the pace from day one in 1983. Most of the subsequent runs were dominated by Yiannis Kouros, whose best time was five days, two hours and twenty-seven minutes. Yiannis was born in Tripoli in Greece, the home of the original marathon. He had a head start in the caper as he just loved putting one foot in front of the other.

Walking is a sport that has always observed the strict COVID-19 protocols, which may still be part of our daily life even in 2032. Walking is something everyone can do even in times blighted by a pandemic. We know how hard it is to walk to school, work or to the beach. The nation can appreciate the effort put in by the long-distance stars.

In the twenty-first century, it is hard to imagine any part of Australia being liveable without a raft of sporting options. At the height of the COVID pandemic, when all sport had been suspended, the leader of the National Party in NSW and deputy premier, John ‘Bara’ Barilaro, stumbled out of the ashes of the summer of the 2019/20 fires and the swamps of the recent east coast floods and admitted that ‘NSW isn’t NSW unless it is playing rugby league’.

That is how important a senior, well-respected politician with a great spread in the Southern Highlands believed sport was to the nation’s most populous state.

Rugby league was a pioneer in the early days of the dreaded lurgy, continuing to play the game. Like horse racing, the league swerved around experts who thought they were mad proceeding with the season and found better experts, more in tune with the thinking of the code’s head office, who thought that the blue paper on Project Apollo (the rugby league season 2020) should be torched for take-off without delay.

One senior member of the Legislative Council, the NSW Upper House, was right up behind the 2020 Footy Frenzy. He was an outspoken advocate of the ‘Bugger COVID!’ press-ahead pressure group. He spoke at length to ABC’s Insiders host David Speers, setting out his case for the Project Apollo blast-off.

Speersie, if we can keep the COVID deaths to around 2,150 per week we should be able to run the whole of the NRL season and stage the Big Dance at Homebush with a crowd of 85,000.

Dave, COVID protocols are not rocket science. The social distancing, the hand washing, the use of the sanitiser bath, we know how to do it. We can all get our heads around it. Plus it won’t be long before we are making a nice dollar from it and exporting our skills to the world.

As to public discomfort, Speersie, the fully ticketed team of specialist Project Apollo staff on the gates at all rugby league grounds can have the public out of their clothes, immersed in a bath of the bug-killing sanitiser gear, hosed off, back in their clothes and seated with a full-strength beer in hand within seven minutes. Most Australians will be prepared to tolerate that degree of state-approved health controls to see a game of rugby league. You wouldn’t object to any of that for you and the kids?

Rugby league players in 2020 responded and generally respected hub life. But as with any ambitious moon shot there are always a few glitches and malfunctions. After all, the players and coaches central to Project Apollo’s success are only human. They have needs. They got hungry. They wandered away from the league-approved chuck

wagon to get their snout into a trough at a local Bar Italia that did the carbonara the way they liked it, as in not too creamy, just the right combo of egg-and-bacon sauce and penne.

But rugby league’s actions give pause for thought at a crucial moment in Australia’s recent history in 2020. After the collapse of fire-ravaged ecosystems, before the east coast was battered by a once-in-a-thousand-years deluge and ahead of the ‘unprecedented’ worldwide pandemic that gripped the nation by the throat, the big topic in NSW politics was the central place of sport in the state’s affairs and the future of rugby league.

COVID revealed how busted-arse most sporting organisations actually were. They had put nothing aside for a rainy day. Head offices across the nation had to slash staff and cut costs. The codes dumped millions from the budgets but asked the nation if they could imagine a modern multicultural, inclusive and diverse society without AFL, rugby league and horse racing in all states. Australia was saved from that catastrophe by very valuable work by club committees at the coalface of the boot. Many right-thinking Australians found themselves asking: If all those great sports stopped, where would the punting dollar go? How would Australia pay for schools, health and cybersecurity?

Politicians and sports administrators argued that all sports were providing a public service to the community. They were solving the mental health issues of the nation. They gave the nation something to think about apart from the annoying germ. Sport gave the nation moving images of humans in action trying their best. These often-spectacular pictures took the mind off the devastation of the recent fires, unprecedented floods and the collapse of the koala population.

Sport gave the nation moving images of humans in action trying their best. These often-spectacular pictures took the mind off the devastation of the recent fires, unprecedented floods and the collapse of the koala population.

The ruling elites know that sport is central to national political life because as well as filling hours of each day with mindless stupidity and offering an opportunity to win big, it offers opportunities for personal redemption. Nothing apart from religion can compete with sport in the redemptive space.

The Fairytale

The Fairytale